It’s been well over a decade since Paul Stone Williams – former president of the church planting organization, Orchard Group (strongly affiliated with Independent Christian Churches), and a one time editor of the Christian Standard – came out publicly as a transgender woman. Unsurprisingly, this self-revelation led to Williams’ immediate and unceremonious sacking with little-to-no recourse.

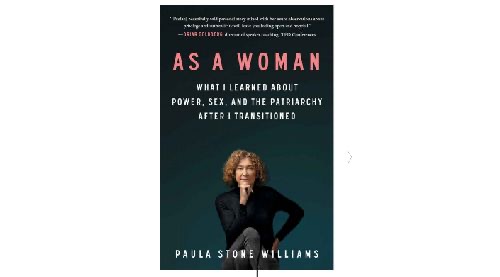

Since then, the sexagenarian has enjoyed a brief flirtation with celebrity as a TED Talk presenter, a media darling to various outlets, morning shows, and news pundits, and as the author of the memoir, As A Woman – What I Learned About Power, Sex, and the Patriarchy After I Transitioned published in 2021 by Simon and Schuster.

In November, the erstwhile CEO of Orchard Group announced that the Envision Community Church – a fully LGBTQ+ inclusive church-plant in Longmont, Colorado which Williams helped start – is shuttering its doors, primarily due to flagging attendance. Apparently, after six years of outreach the church was unable to attract and retain families with children.

As it happens, I managed to read Williams’ book, a carefully crafted and, at times, even compelling read. I have no doubt that many will see themselves in this tale.

What’s vexing, however, is the contemptuous tone the author now takes toward the same evangelical Christianity Williams spent a lifetime proliferating. Even more troublesome are the unseemly alter calls beckoning audiences to rally around Williams’ conversion – a multimedia crusade retailing a more ‘generous’ and ‘authentic’ brand of spirituality. A generosity, however, quickly belied by the author’s uncharitable trafficking in lazy and dishonest stereotypes of the Christian faith. Page after page of reductive tropes are marshaled in defense of Williams’ rebirth. Twenty-nine times the words “fundamentalism” or “fundamentalists” are employed to describe former friends, family, associates – an entire brotherhood. But fundamentalism loses its pungency when it is used to mean, pure and simple, Christianity.

Sadly, Williams’ transubstantiation is just the latest in a long line of vulgarians desperately trying to win respectability.

In terms of persuasiveness, As A Woman has been cautiously summarized as, “A transgender woman chronicles her difficult journey from ‘alpha male’ and evangelical leader to life in the body that feels most natural to her.” A sentence skillfully crafted in Talmudic distinctions.

For this reader, Williams’ stilted prose – which, at times, appears to be written by someone seeking to convince themselves of their own happiness – fell far short of its desired goal. A disappointing reality for one so noisily and sanctimoniously invested in their own unassailable authenticity.

The chapter on Gender and Sexuality in particular, for all its grandiloquence, fails in its effect. What is intended as a convincing expression of undeniable femininity, comes across, instead, as little more than the ham-fisted attempt to appropriate the delicate female sensibility of sexuality.

A beauty men do not understand and cannot possess.

It is difficult to believe that this author once served as the editor of what was our national periodical. Surely Williams can write better than this. Seriously, for the most revolutionary transformation in one’s life to climax in reductive cliches about Christians fearing what they don’t understand – I just don’t believe it. More to the point, I don’t believe Williams believes it.

Don’t get me wrong, I am not suggesting that Williams is cosplaying. I believe Williams’ feelings are real. Indeed, gender dysphoria is all too real. So too, those who suffer from body dysmorphic disorder and anorexia nervosa. All are marked by persistent shame based obsessions over perceived body defects often resulting from childhood trauma. In fact, it’s no surprise that a significant comorbidity rate of eating disorders exists among those who unconsciously choose to reject their own gender. The early chapters of this memoir describe convincingly the formative years of someone living with the effects of early-childhood trauma. What’s more Williams describes, at times in vivid detail, just how that trauma continues to strain “her” hold on reality.

Make no mistake, the deficiencies in Williams’ upbringing is a heartrending narrative deserving of our prayerful compassion.

It is not, however, an unfamiliar one. Hope exists for those who seek it.

As an adult, Williams’ fifteen minutes of fame now seems far more Faustian than what was widely appreciated at the time. The book tells of behind-the-scenes production meetings with TED Talk executives, coaches, and public relations experts. Meetings that preceded and informed Williams’ baptism into the amniotic fluid of secular humanism and the modicum of notoriety that followed shortly thereafter. Beholden to a new master, nothing and no-one in Williams’ ambit was too precious, too cherished to escape being sacrificed at the alter of Williams’ ambition. To be sure, Paul cruelly burned down his previous life . . . in its entirety.

Today Williams speaks of living life wholistically, free of shame. But the reader is never informed of how ridding oneself of this shame has made Williams a better person. One may wonder for instance, ‘How – exactly – does learning to love yourself translate into being a more lovable person?’ ‘You may well have learned the difficult lesson of loving yourself, but have you increased your capacity for loving anyone else?’

Williams seems pretty confident that Christianity’s teachings are the problem. But I can’t help but wonder about the solution. When a person claims to have learned to love oneself, to which ‘self’ does this refer? Does Williams refer to the ‘self’ that God used in expanding the Kingdom in face of spiraling church attendance nationwide? Is it the ‘self’ that faithfully instilled the Word of God in his own children while successfully managing a painful mental disorder? Is it the ‘self’ that earned the trust and respect of thousands of Christians once expressed in millions of dollars of largess? Or does it refer to the ‘self’ that walked away from all of that?

In all sincerity, away from the fog of the culture war, away from boycotts, away from in-store displays and social influencers, these issues bear sobering implications for the people who come into Williams’ life and, therefore, deserve to be addressed.

So for the people who know and love Williams, for those who daily risk the potential devastation unleashed by these choices, what of their desires? Do their desires merit any consideration?

Are their ‘selves’ any less deserving? What of their mental health?

Forgive my impertinence, but when you report having discovered a life free from shame, I have to ask, is it also free from the intrusive thoughts asymptotically promising ‘just one more dose of hormone’ or ‘just one more nip and tuck’ but never leading to any lasting satisfaction?

I mean how does one claim to achieve the peace and tranquility that comes with self-acceptance, while leading in an ongoing conspiracy of incremental self-annihilation? (It’s like some sadistic version of Zeno’s paradox: the closer you get, the further away you are.) How does one justify the dark, elegiac tones when referring to one’s former self? There is precious little nuance, afterall, in the phrase “dead naming.” For that matter, how – exactly – can one devote an entire autobiography to the subject of transgenderism, entitle the last chapter For The Greater Good, but never once mention the soaring rates of suicide and suicide attempts associated with transgenderism – particularly among America’s gender dysphoric youth? Suicide rates, by the way, that seem impervious to gender affirming therapies.

Throughout the entire book, the solitary reference to suicide involves Williams’ solipsistic browbeating of a well-intentioned and situationally aware therapist.

Why, you ask?

For the unpardonable sin of calling 911 after Williams left an ambiguously worded voicemail and then neglected to acknowledge her callbacks.

In fact, if there is a single metaphor that summarizes this entire installment of Williams’ life, that’s probably it – not a flattering one.

Ultimately, I can’t help but believe that Williams still has a great reward stored up in heaven – especially in light of the confident leadership Paul provided to so many for so long. It’s mind-bending, frankly, to think that someone could throw away that confidence at such a late stage in the journey.

Amazingly, the Word of God anticipates even this when it says, “Therefore, do not throw away your confidence, which has a great reward.” – Hebrews 10:25